Russian ISIS lurks under Islamic titles

As Russian speaking jihadist networks adapt to evade detection on social media, the need for advanced AI to identify these threats becomes increasingly valuable for counterterrorism efforts.

Executive Summary: This article explores how jihadist networks have adapted on social media to evade detection, posing significant challenges for counter-terrorism efforts. These networks have rebranded themselves under legitimate-sounding titles, making it difficult to distinguish between benign and dangerous groups. The complexity is exacerbated by legal protections for religious freedom, which hinder efforts to shut down networks based solely on their religious content. Advanced AI is seen as crucial in addressing these challenges by analyzing multilingual and culturally nuanced data to detect extremist activities effectively. The article also discusses regional responses, such as varying policies towards Islamic practices, and emphasizes the need for a balanced approach that respects human rights while countering extremist ideologies.

Adapting Jihadist Networks: Challenges and AI Solutions in Counter-Terrorism

On social media, jihadist networks have been blending into legitimate communities, making it difficult for counter-terrorism efforts to identify and monitor them. To effectively address this growing threat, there is a need to advance our technological and cultural understanding to enable AI to play a crucial role in counter-terrorism operations.

In the aftermath of global counterterrorism operations against ISIS, the virtual jihadist community has been forced to adapt. Those who escaped imprisonment or death on the battlefield have developed methods to hide in plain sight on social media. These rebranded networks now operate under legitimate-sounding titles. Consequently, distinguishing between benign and dangerous groups has become more challenging for counterterrorism efforts.

Around 2014, jihadist social media presence was at its peak, and while the international community recognized the problem, there lacked concrete legal solutions or plans in place to address it. For the Russian-speaking jihadist community, groups were openly named “Caliphate” or “Islamic State.” Al-Nusra supporters used variations of names like “Al-Sham.”

As global counter-terrorism efforts intensified, targeting recruitment platforms, social media accounts, and cyber-criminal networks, jihadists began creating new groups with less obvious titles. Over the past few years, these members have been lying low and expanding their networks. They aim to revive Islamic State’s organized terror and al-Nusra’s disorganized chaos by stealthily returning to social media.

By leveraging legal and linguistic nuances, these users have become adept at navigating the cyber environment. Many group names now include terms like “Islam” or interest queries such as “religion,” and other innocuous references to the Qu’ran and Hadith. This makes it difficult for nations to shut down these networks due to strong protections for religious freedom and speech. This is especially true for European and American governmental systems that battle for privacy laws.

Groups like “Al-Islam” appear to be ordinary communities for Muslims. This academic chat is run by Dr. Ihsan who answers questions from subscribers and explains aspects of the Qur’an and Hadith. Mainly, Al-Islam is a platform for Russian-speaking Muslims seeking religious education. Al-Islam is open to the public, a rarity these days for groups with potential terrorist links. However, the broader themed open channels tend to feed the more nefarious accounts with shared subscribers.

Social media accounts requiring administrator approval for access often raise suspicion. For example, the Russian language Al-Furqan, which has existed for several years, is currently set to private. The administrator may have legitimate reasons to exclude Russian hecklers from insulting or harassing the platform. However, deciphering where counter-terrorism efforts should focus is increasingly difficult as many of these private channels appear unobtrusive on the surface.

However, if you Google Al-Furqan, there will be a flurry of results. Al-Furqan is the 25th chapter of the Qur’an, and in English it means the Criterion. Surely there are discussions on jihad on these websites and groups that have nothing to do with terrorism. This is precisely why the nature of hidden networks lurking in plain site is challenging for countering terrorist activities.

Another difficulty is the religious nature of the discussions, necessitating deep knowledge of Islam. There is a distinction between general Islamic teachings, Wahhabism, and the ideologies of Islamic State and Al-Nusra within the Russian Muslim community. Al-Furqan professes a Wahhabi interpretation, but not necessarily evocative of violence. The trick for counterterrorism operations is that among the zealous subscribers are terrorist networks. Without leveraging Dark web OSINT, the main path to determine the group members, is to join and listen, which is a whole other can of worms.

As technology advances, human strategies to circumvent detection also evolve. On the one hand, algorithms have improved to detect political or social issues on social media to either ban or minimize reach. While algorithms have improved in identifying political or social issues on social media, users find ways to navigate around these systems. Until AI can precisely analyze multilingual audio, human analysts will remain essential in identifying the ideological proliferation that led to the societal blackhole of ISIS and AQ.

Despite Russian efforts, the region’s Muslim population has increasingly leaned towards Wahhabism over the past two decades. President Putin has the support of Chechnya, which is a cultural impactful society in the North Caucasian community. Chechen President Ramzan Kadyrov’s promotion of a self-described non-Arab “Chechen Muslim identity” enforces measures to distance its people from Wahhabi culture. For the Chechen government, Wahhabism is synonymous with terrorism.

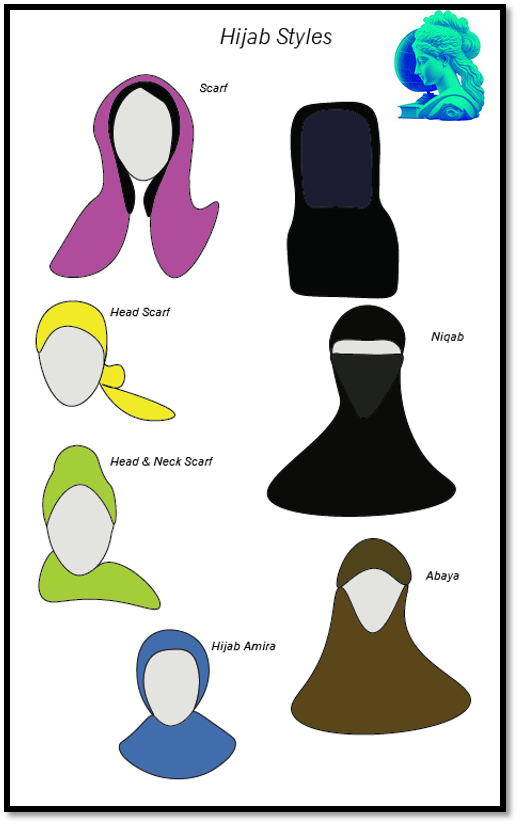

Tajikistan, while more secular than Chechnya, is set to ban many hijab styles, allowing only traditional headscarves. The Tajik government claims that hijabs of Arab lineage are not part of their indigenous culture, aiming through legal measures to protect their people. This move follows four months after the Crocus City Hall massacre involving ethnic Tajik networks. By restricting religious freedom, Tajikistan and Chechnya are attempting to counter terrorism by eradicating Wahhabi cultural influences.

In part, this results in the extremist networks ability to attract potential followers under the perception, which is reinforced by these laws, that Islam is not allowed in their home countries. The restrictions of COVID requiring all people to wear masks only fuels the fire of prejudice against niqab. Outside of Central Asia and the Caucasus, the support for Wahhabi trends appears to prevail in Eurasian Muslim diasporas in Europe.

This is especially evident in countries such as France, Germany, Austria, Turkey, and Poland. One gauge is the trend of women's hijab, which is a topic I have written on in more detail for the Cyber Defense Review at West Point. The Central Asian and Caucasian hijab styles of the 21st Century tend to involve colorful headscarves, and form-fitting dresses. The styles more popular among Eurasian Wahhabi culture today, such as muted brown and black shades of abaya, niqab and, the rarer burqa, are associated historically to the Arab Gulf States like Saudi Arabia, Qatar, United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, and Kuwait. However, in the context of Arabian Peninsula culture, niqab has no terrorist connotation let alone an indicator for extremism.

Niqab is a hijab style associated with extremism in Russia, so it is interesting that in late May 2024 Russian courts declared wearing the veil permissible in the Russian Federation. The court found no empirical link between wearing the niqab and terror-related jihadism, viewing a ban on the niqab as a violation of human rights and religious freedom. This rationale stands out in Russia where homosexuality is illegal and the LBGTQ movement is under surveillance.

The decision by the Russian court, supported by President Putin, suggests a preventive, strategic move to temper potential unrest among the Muslim population. President Putin does not speak against Wahhabism directly, which would be offensive to the Gulf States with whom Russia does business. The rise of ethnic Avar Khabib Nurmagomedov from Dagestan on UFC for Mixed Martial Arts, who practices a conservative form of Islam, and his direct, calm messages on Islam and his people, may have influenced President Putin's view on the subject.

There is a balance between leaving groups on the fringe of society room to express themselves. As it does in the world of physics, it serves society to permit a low-level of temperance for extremist discussion to prevent societal implosion. This is precisely the implosion point which led to the massive onslaught of ISIS supporters from Eurasia nearly ten years prior.

On the bright side, AI can be counterterrorism's best ally. The better we analyze and understand the cultural outliers of hidden networks, the more detail and nuance the data sets can have to train AI. In the world of statistical linguistics and audio translation, there is still room for improvement, but the time is nigh for audio-enabled AI in the counterterrorism realm for a safer cyber environment. This translates to a more stable, physical environment in reality.

To effectively combat the evolving threat of jihadist networks on social media, it is essential to enhance our technological capabilities and cultural understanding. By advancing AI technologies to accurately analyze multilingual and culturally nuanced content, we can improve our ability to detect and counter these hidden threats at the velocity of growth. As we continue to refine AI for counterterrorism purposes, we must also ensure that our efforts respect human rights and foster global cooperation.

~E

Gray Truths©️2024