The complexity of hijab bans in CT

The unintended consequences of hijab bans, such as Tajikistan's latest decision, may fuel extremism and terrorism.

Executive Summary: In 2018, I published an article warning of the connection between hijab and terrorist recruitment, entitled Culture in a Murky World: Hijab Trends in Jihadi Popular Culture for the United States Military Academy at West Point's Cyber Defense Review. In this expository piece, I argue for the necessity of cultural analysis in counterterrorism efforts by showcasing cultural analysis of hijab-themed jihadi content from open-source information aimed at Muslim women in Eurasian communities. When governments ban or restrict hijab, which is a deeply personal issue for women, it isolates Muslim societies and consequently fuels support for extremist groups.

Recently, Tajikistan's ban on hijab, intended to protect cultural norms and counter Salafi trends, has highlighted the sensitivity of this issue in Muslim communities. A counter-culture social wave against the ban, as well as Dagestan’s niqab ban, has the potential to strengthen jihadi-related terrorist networks. When governments focus on the hijab as the overarching problem, it distracts from the root causes of terrorism such as corruption, poverty, and deeper socio-cultural issues. Terrorist organizations exploit these problems to activate networks. Adding religious suppression exacerbates online jihadist activity, which is a precursor to violent attacks in Eurasia, Europe, and the U.S.

Hijab Bans in Eurasia: A Catalyst for Extremist Recruitment?

On June 24, 2024, the Muslim-majority nation of Tajikistan officially banned the wearing of the hijab under the principle of protecting indigenous cultural norms. Tajikistan, which has persistent issues with jihadi-extremist ideologies, is the home nation of the five individuals involved in the Crocus City Hall ISIS-K attack in Moscow. The Tajik government’s decision restricting hijab is also related to countering extremism by suppressing modern Salafi Islamic trends.

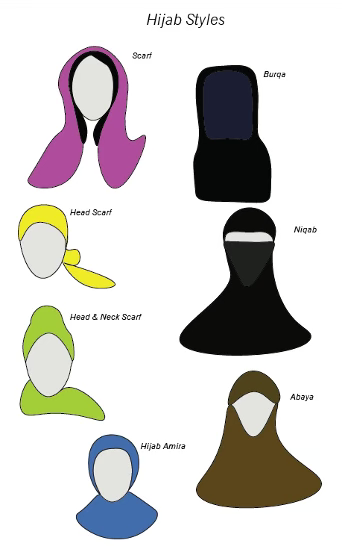

The sub-cultures of Salafi or Wahhabi movements in Islam, which have historic roots in the Arabian Peninsula, have been gaining popularity among Eurasian Muslims. A distinctive aspect of this sub-culture is a dress code that requires women to wear loose-fitting cloaks, such as the abaya, typically in black or brown, as bright colors are considered provocative and inflammatory. While the burqa is uncommon in Salafi sub-cultures, the black face veil (niqab) is more socially accepted and even obligated by some clerics.

Nearly two weeks after the extremist attacks in Russia’s North Caucasus, Chief Mufti of Dagestan Akhmad Abdullayev announced that the region would temporarily ban the niqab. The ethnically Slavic Russian governor Sergey Melikov supports the decision, viewing the niqab as "Arab culture" and as a security risk. Keep in mind that Mr. Melikov also blamed a ‘U.S.-led Western conspiracy’ for the gunmen attacks in Makhachkala and Derbent that killed 21 people in June, as well as the Crocus City Hall ISIS-K attack killing 200.

In reaction to Tajik President Emomali Rahmon’s anti-hijab stance, Ramzan Kadyrov, the President of the Chechen Republic in the Russian Federation, condemned the ban. While the Russian court has yet to ban the niqab, Russian official Alexander Bastrykin recently argued for a national ban given the attacks in Dagestan, much to the ire of Mr. Kadyrov. The Chechen president argues that Islam and the niqab have no connection to extremism, and that extremists are fanatics, not Muslims.

Although the republic has not technically banned the niqab, Chechnya’s position on this topic is peculiar. The Chechen government forcibly advocates a style of Chechen hijab, or a loose-fitting headscarf, for women. Chechen women are not necessarily free to wear the black niqab in public without attracting police attention due to its association with Wahhabism.

The Chechen government vehemently opposes Wahhabi culture, holding it ideologically responsible for separatist movements and extremist networks. Over the last two decades, Chechen counter-terrorism police forces in conjunction with Russian KTO have effectively squeezed many extremist networks out of Chechnya, pushing them into Dagestan, Turkey, Central Asia, the U.S., and Europe. As a result, Western nations that permit religious freedoms are targeted for the societal transgressions of foreign governments.

For international counter-terrorism efforts, the challenge lies in identifying when the hijab, and which style of hijab, indicates more than cultural or religious piety. However, there is historic precedent for variations in face veiling practices across North Africa, Turkey, the Balkans, and Eurasia. It begs the question: is the issue the hijab itself, the niqab, the ideologies of the extremist groups for whom it is an emblem, or the security environments in which extremist networks thrive?

Balancing this issue is increasingly important for democratic nations in the fight against terrorism. In countries like France, Orthodox Jewish women cover themselves at the beach, but Nice's municipality banned the burqini. To Muslim communities, it becomes clear that Muslims are not treated equally, which creates a baseline for extremist recruitment. Still, the subject of hijab is not weighted equally across all Muslim communities and nations.

Iranian women are being imprisoned and dying in police custody for not wearing state-approved hijab. For instance, a Kurdish-Iranian woman received 74 lashes for refusing to cover herself in a religious cloak. Meanwhile, some Turkish women are reveling in joy after Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s government lifted the hijab ban in 2013 in Turkish government and university buildings.

The hijab is a highly sensitive and powerful topic in Muslim society. Extremist groups recognize the emotional influence of this topic and feed off modern Salafi movements. Banning the hijab and its many variations strengthens extremist organizations by providing a stronger justification for their recruitment content.

If Muslim communities are disproportionately targeted due to their religion, even in nations where the dominant religion is Islam, it validates the conversations in extremist forums. These groups then argue, with evidence, that democracy and religious freedom only apply to some. Consequently, religious suppression overshadows the core problems of jihadi-related terrorism.

The more relevant points on criminality, corruption, and culture are lost in these hijab-centric discussions aimed at countering terrorism. Whether or not an extremist or terrorist is a Muslim is an omnipotent judgement, just as with Christians, Hindus, Buddhists, or Jews who commit crimes. What is clear, however, is that individuals who commit legal offenses under the rule of law that defines domestic and international terrorism, are criminals.

In nations with high levels of criminal activity and jihadi-extremist sub-cultures, there are corresponding levels of government corruption and instability. This corruption leads to a range of governance issues: economic problems, unemployment, and a lack of justice and transparency in law enforcement. Consequently, extremist activity perpetuates, accentuating instability through armed conflict, as in Dagestan’s case.

Lastly, there are deeper cultural issues wherever there is local tolerance for jihadi-extremist groups. The Malaysian community effectively demonstrated the impact of local, community-oriented projects focusing on the socio-cultural issues leading to extremist support. Conversely, Indonesia permits niqab and hijab, which hosts the largest Muslim population globally, providing some valuable lessons to learn.

By permitting and safeguarding religious freedom, and continuing to evolve and enhance counter-terrorism efforts, nations like the U.S. can mitigate divisiveness and reduce extremist propaganda. However, if extremist entities are unable to operate in their home countries due to intense policing and unresolved governance issues, terrorist attacks will occur in free nations as an expression of contempt for their native governments. Therefore, it is equally important for nations like the U.S. and other democratic-minded nations to urge other nations to permit religious freedom and address corruption.

Focusing on the hijab, which is sentimental and religiously significant to people, distracts from the root problems that extremist organizations leverage for recruitment. Since governments can only address issues like corruption and security, international counter-terrorism efforts can use cultural analysis and open-source information to enhance their effectiveness. This approach broadens situational awareness and improves the identification of indicators and warnings in a more nuanced manner.

Cultural analysis helps direct where counter-terrorism efforts should focus their energy and resources. Truly analyzing and understanding the sub-cultural details helps distinguish between physical threats and benign elements. This is especially pertinent when dealing with complex issues such as the global, ethnically diverse murky world of jihadist networks.

Unfortunately, governments weaponize the topic of hijab, affecting people in a deeply personal and complex manner. As a result, the Russian Federation and Central Asia are not the only regions that will feel the impact. Europe and the U.S. are likely to experience an increase in online jihadist activity and network growth following official bans like those in Tajikistan and Dagestan. Increased recruitment often precedes terrorist attacks.

It was an honor to publish for West Point's Cyber Defense Review on the significant role of hijab in emerging security trends. It is important to continue and highlight this conversation for the sake of international and domestic defense and security.

~E

Gray Truths©️2024